Exploring unknown territories

Chase Weidmann had three goals for a career: do something “cool,” improve the lives of other people, and, of course, be able to support himself.

Weidmann found the “cool” in high school science classes and he quickly realized that biology and `biotechnology offer vast uncharted territories to explore. One such uncharted area was the academic system itself, as he sometimes struggled to navigate his way through college. Still, he was very glad to find that stipends and resources would enable him to continue exploring in graduate school. He pursued his doctoral research at the University of Michigan (U-M) where now, a decade later, he is joining the RNA faculty community as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Chemistry and as the second hired RNA Scholar Faculty of the Center for RNA Biomedicine.

Weidmann found the “cool” in high school science classes and he quickly realized that biology and `biotechnology offer vast uncharted territories to explore. One such uncharted area was the academic system itself, as he sometimes struggled to navigate his way through college. Still, he was very glad to find that stipends and resources would enable him to continue exploring in graduate school. He pursued his doctoral research at the University of Michigan (U-M) where now, a decade later, he is joining the RNA faculty community as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biological Chemistry and as the second hired RNA Scholar Faculty of the Center for RNA Biomedicine.

From his first encounter with math, science, and technology in a Wisconsin high school, Weidmann generally knew that science was what he should study, but he had little idea about how to turn this interest into a career. Which scientific field could both captivate his interest and lead him to his second goal of helping people and positively impacting society? As a young undergraduate at the University of Rochester in New York, he was introduced to the wonders of RNAs: their roots in the origin of life, their critical role in the translation of proteins, and indeed their great therapeutic potential.

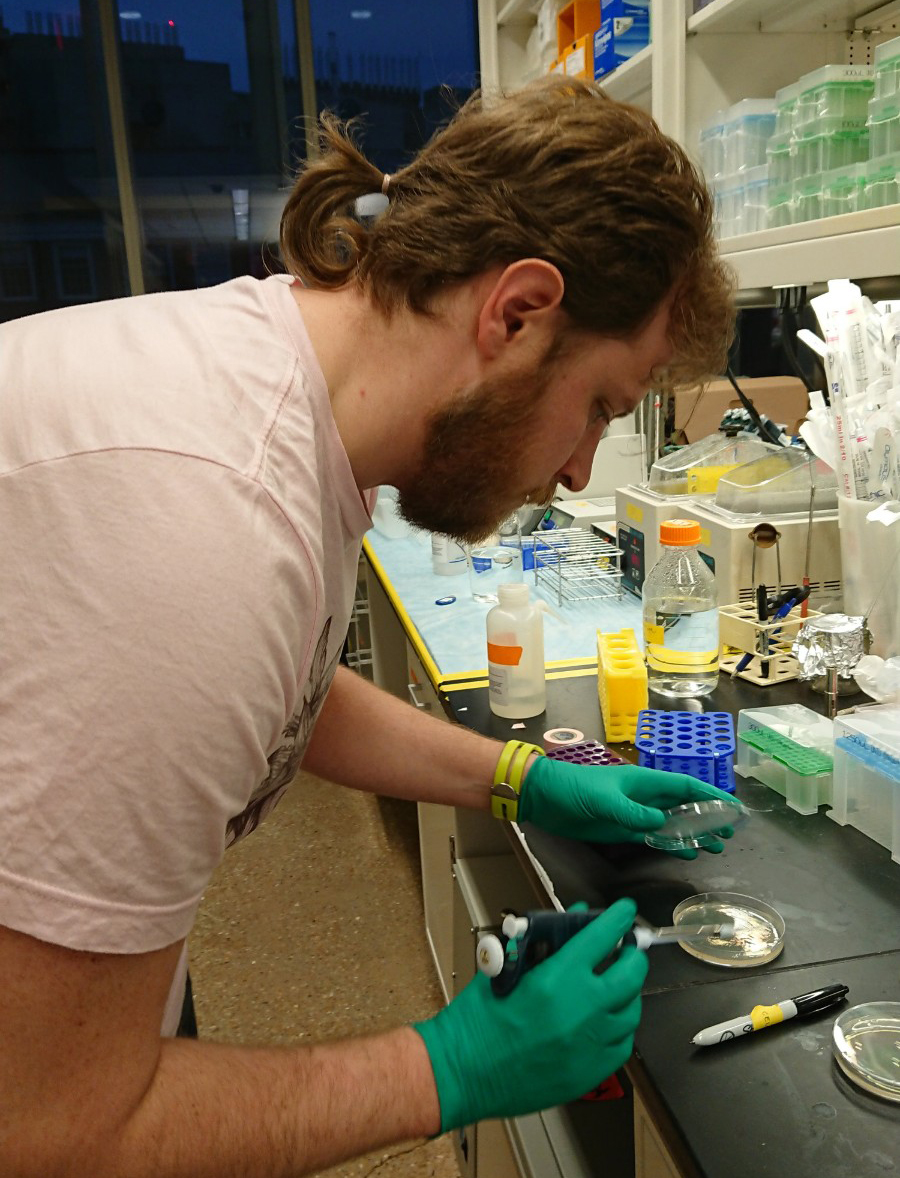

RNA-protein interactions naturally became his first rotation topic when he joined the University of Michigan for his doctorate studies, in 2009. He explore two vastly different areas of cellular biology in his rotations, namely in cellular trafficking and protein chaperones, but he quickly realized that RNA remained his true passion. He completed his doctorate dissertation on mechanisms of messenger RNA regulation by the RNA-binding proteins Pumilio and Nanos, with Professor Aaron Goldstrohm in the U-M Department of Biological Chemistry. Weidmann explained that at the time, another class of RNA, long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), constituted its own vast uncharted territory that was quickly becoming the new frontier of RNA research. “People used to think that non-coding DNA was just junk, then it turns out that most of it is actually transcribed into RNAs. Even if only a small percent of these transcripts are functional, this represents a vast untapped ocean of potential therapeutic targets. Obviously lncRNA research will make a huge impact in the understanding and curing of diseases like cancer.”

As a postdoctoral fellow at the University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill, Department of Chemistry, in Kevin Weeks’s lab, Weidmann dove into new research on lncRNAs, and became specifically interested in the way they interface with protein to accomplish cellular functions or, in the case of cancer cells, promote deadly metastases. While many smaller non-coding RNAs can form tight stable structures, many lncRNAs contain unstructured “noodle-like” domains that can interact with a number of different proteins. In a cancer cell, unstructured lncRNA domains in the wrong place at the wrong time can bridge together proteins where they should not, contributing to the further proliferation and metastasis of tumorous cells.

For studies of lncRNA function and dysfunction, Weidmann developed in-cell probing assays that use chemical compounds to mark RNAs either according to their structures or their protein binding networks. These technologies help pinpoint the parts of lncRNAs responsible for their activities. With the help of the Center for RNA Biomedicine SMART Center, Weidmann plans to visually track these lncRNA-protein assemblies to understand how they can wreak havoc on gene expression.

At the U-M Department of Biological Chemistry, Weidmann is now building his lab to further research RNA-protein pathways that could eventually become therapeutic targets. Weidmann’s hope is that new treatments might be developed with the help of other U-M experts and collaborators. “RNA has such a big footprint, it will be very easy to find collaborations at U-M, especially with the support of the Center for RNA Biomedicine.”

Mentoring

Weidmann is grateful for the effective and generous mentoring he has received all along his career. Mentoring has helped him navigate academia and build his confidence. Late to begin his career in research, his undergraduate advisor, Elizabeth Grayhack, took a chance on Weidmann and gave him his first independent project in her own laboratory. Starting in the lab, he fondly recalled the amazing lab tech who taught him to not rush and plan his time.

Early in Weidmann’s graduate studies at Michigan, Professor Aaron Goldstrohm frankly laid out for him the milestones to become a principal investigator. “A lot of my success has been with the luck of meeting the right person at the right time. Mentorship is very important; working hard is of course also key, but it is only a small portion of the success equation.” Those experiences have been very determinant for Weidmann who is highly motivated to become a mentor himself and help students and junior scientists avoid the mistakes he made. Already, one of his recommendations to students is to develop the confidence to reach out to faculty and other potential mentors, as he feels he missed out on too many opportunities due to “imposter syndrome.” Weidmann feels that actively engaging students who might have a hard time reaching out is critically important in addressing challenges in diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in academia, and he hopes to make a difference through his leadership and hiring opportunities in his laboratory and as a faculty member.

Weidmann recognizes that we have reached a historical moment when people are reconsidering the values by which they live. He believes in “living our best lives and in doing our best work,” which he thinks can be better achieved with flexible hybrid working and learning model, as well as with leveraging the technologies that enable them. Weidmann imagines many innovative ways to deliver science. He is interested in exploring alternative approaches to train the next generation of students, while still preserving mentor-mentee, one-on-one, and small group opportunities, whether it be though dedicated teaching assistants in the classroom or on-demand virtual office hours.

Weidmann feels deeply rooted in the mid-west and is delighted to be back. He got married in Ann Arbor during graduate school, to another biologist and (almost) mid-westerner. The University of Michigan is halfway between Weidmann and his partner’s hometowns. Even in hobbies, Weidmann has a restless mind: he is a big fan of video and board games that present various levels of complexity, story-driven narratives, and opportunities for both collaborative and competitive play. More recently, he began acting as game master for his first Dungeons & Dragons roleplaying campaign, something he finds stimulates his creativity and on-the-fly thinking in unexpected ways. Gamification, as both a teaching tool and as a way to harness gamers’ problem-solving ability, is increasingly being applied to scientific questions, including for understanding RNAs. It is no surprise: creativity, curiosity, and perspective shifts are key skills to solve scientific problems and will no doubt serve well on the next scientific frontier.

READ Dr. Weidmann’s scientific feature

WATCH his introduction video